The third in a series of articles by our Northern California Waldorf Teachers Conference Keynote speaker Michael Howard.

Having introduced the idea of an artistic way of knowing as the complement to a scientific way of knowing, we now turn our attention to another realm of knowing: the capacity to know our self. We cannot speak about self-development without cultivating self-knowledge based on self-observation. We will consider the observation and development of our self as an artistic activity requiring artistic capacities. Today, self- development is widely understood as something mature adults take up for their own wellbeing and fulfillment, as well as to better serve the needs of the world. There are so many forms of self-development that it can be both exhilarating and bewildering to find our way through the many possibilities. Even Rudolf Steiner has written and lectured about so many different paths and exercises that it can be hard to find our way.

Many people are so aware of their limitations and apparent lack of development that they tend to under-estimate their inner progress, while others are inclined to over-estimate themselves and their accomplishments. In both cases, we under-estimate or over-estimate ourselves because we fail to see what is most important in our development. For this reason, I want to draw attention to an essential aspect of our inner work that tends to be overlooked. Rudolf Steiner said something to the first Waldorf teachers, just days before opening the doors of the first Waldorf school in 1919, that can point us in a fruitful direction:

You can only become good teachers and educators if you pay attention not merely to what you do, but also to what you are… we must become conscious of this first of educational tasks: that we must first make something of ourselves, so that a relationship of thought, an inner spiritual relationship, may hold sway between teacher and the children.

Rudolf Steiner, Study of Man, 1919, p. 23-24

To be effective teachers, it is not enough to focus only on what we say and do, but above all else, “we must make something of ourselves.” What does this mean? At the very least, Steiner is suggesting that our own development is not a personal matter but is central to serving the development of our children. The quotation from the Younger Generation lecture that I brought in the first article sheds light on what it means to make something of ourselves:

All instruction must be permeated by art, by human individuality, for of more value than any thought-out curriculum is the individuality of the teacher and educator. It is individuality that must work in the school…and Art is the awakener…

Rudolf Steiner, The Younger Generation, Lecture 11, p. 142-145

To make something of ourselves means to awaken and develop our spirit individuality, so that individuality permeates our teaching and the school community as a whole. This is reason to clarify our understanding of individuality, and how art can be the awakener of our individuality. In what way can art be a path of inner development?

Near the beginning of Knowledge of Higher Worlds, Rudolf Steiner unexpectedly uses the term “artistic feeling” when speaking about the development of spiritual faculties:

It should be remarked that artistic feeling, when coupled with a quiet introspective nature, forms the best preliminary condition for the development of spiritual faculties.

Rudolf Steiner, Knowledge of Higher Worlds, p. 41-42

In the previous article, I quoted Rudolf Steiner speaking about artistic feeling when looking at artistic forms like those in the First Goetheanum, but also with the raindrop and balloon forms I brought. In this new context, we might well ask: What does artistic feeling have to do with the development of spiritual faculties?

In another context, we could address this question through Rudolf Steiner’s sculpture, The Representative of Humanity. Seen through the lens of artistic feeling, this sculpture can be experienced as a living imagination of our spirit individuality, our Spirit Self. However, for this article, we will instead look at another form exercise that in a simplified, but no less real way, can awaken an experience of our spirit individuality.

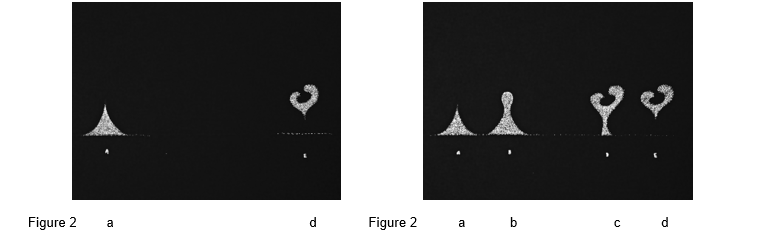

We can observe form 2a as being widest at the bottom, with concave sides coming to a point at the top. Form 2d is wider and convex in its upper part while coming to a concave point at the bottom, and it is open in the upper middle. Noting these different form elements can help us experience the qualitative gesture of each form through artistic feeling, not just our personal feeling of like or dislike. Form 2a is not moving down as with the raindrop form, but is withering in lifeless weight. Form 2d is not simply rising as with the balloon form but is flying away with open expansiveness.

To begin with, it is sufficient to limit ourselves to such simple qualitative descriptions of these forms. However, a further enrichment is possible if we ask: When in everyday life do we have feeling experiences likes those embodied in forms 2a and 2d?

When we pay closer attention to the dynamic quality of our inner life, we can recognize some situations where we feel weighed down, while in others we feel buoyed up. For example, sometimes we might feel under-confident because we under-estimate our selves, while at other times we may feel over-confident because we over-estimate our selves. What is the inner gesture of over-confidence compared to under-confidence? If we look at forms 2a and 2d as capturing something of these two inner dynamics, which feels more like over-confidence and which feels more like under-confidence? I have never heard anyone suggest that under-confidence feels expansive or over-confidence feels contracted, but the opposite.

In his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle speaks about virtues and vices, only he speaks of two kinds of vices that he calls: vices of deficiency and vices of excess. One example he offers of a virtue is confidence, with under-confidence a vice of deficiency and over-confidence a vice of excess.

Today, we may not readily connect to the terms virtue and vices, but there is another way to approach this important phenomena that is more contemporary. What is the problem with feeling under-confidence or over-confidence? Are they not simply part of human experience? If we reflect on such experiences, we may observe that in both under-confidence and over-confidence we feel less free, while in confidence we feel more free in our self.

As inner freedom is a central issue of our time, it is a very practical insight to realize that we can be inwardly unfree in two ways: we can be unfree in deficiency or unfree in excess. Another triad can help us see how an unfree state can be transformed into a free one:

Cowardly Courageous Reckless

When feeling cowardly we are unfree through our lack of courage, or what I will call, under-courage; when feeling reckless we are unfree through an excess of courage, or over-courage. However, courage is not something we step into like a pair of shoes, it requires an inner effort at overcoming cowardliness or recklessness. How do we this? To be courageous when we are cowardly, we must summon from within ourselves some expansive inner fire to overcome our inner paralysis. Similarly, when recklessly hotheaded, we must inwardly pour some cold water on our impulsive fieriness. In either case, the path to inner freedom lies in learning to balance an unfree attribute with its opposite.

The idea that we can cultivate inner freedom by calling up an opposite quality to an existing unfree quality may sound simplistic and formulaic, but it is only a starting point. The lived reality of bringing expansiveness to contractedness, or the opposite, usually involves many failed attempts before achieving some modest success. Many of us learn the slow and hard way to calm ourselves when we are too agitated, or to prod ourselves into movement when gripped by inertia.

The moments when we initiate self-equilibrium, however feebly and fleetingly, are among the most significant accomplishments of our lives. It changes our experience of our self, as well as the dynamics of our relationships with others. A further significant dimension reveals itself when we ask: What self initiates such an inner transformation from an unfree to a more free state in our self?

When we speak about body, soul and spirit, we are clear that body refers to our outer physical nature, while soul and spirit refer to our inner self. Most people use soul and spirit as synonyms, but in reality they refer to two distinct aspects of our inner self. To clarify this conundrum, I use personality as a synonym for the human soul, and individuality for the human spirit. Our soul personality refers to all that we identify with as our thinking, feeling, and willing. Our spirit individuality is what we, and only we, call “I.” It is not uncommon for us to observe our thinking, feeling and willing, but who is observing the content and activity of our soul? It is “I” who observes my soul. In that moment, “I” know through direct experience that “I” am not my thinking-feeling-willing soul; I am a spirit individuality.

We will conclude with two important observations:

- The activity of perceiving unfree qualities like the contraction of under-confidence and the expansiveness of over-confidence, and bringing balance and wholeness within our self is an artistic activity. In this sense, we can speak concretely of self-development as an art.

- If self-development is an art, what is the artwork and who is the artist? Our soul personality is the work of art; our spirit individuality is the artist of our self. However, slow and imperfect, the artistic transformation of our soul personality is a key way we develop our spirit individuality.

Awakening our spirit individuality through artistic capacities and activity is to make something of ourselves in a way that is especially suited to the needs of our time, and yet, is largely overlooked and underappreciated by our selves and others. No matter how limited or thwarted we feel by outer circumstances, even our most feeble efforts at becoming inwardly free is a contribution to human evolution, and most directly a gift to the children we serve. I imagine Waldorf schools as developmental communities where young and old can authentically be open and trusting with each other on their mutual paths of self-realization.

In the fourth and final article, we will explore more specifically how Waldorf schools can play a leading role in the cultural metamorphosis of communities founded on commonality to communities founded on individuality.