The second in a series of articles by our Northern California Waldorf Teachers Conference Keynote speaker Michael Howard.

Forget everything you thought you knew about the difference between the hemispheres (of the brain) because it will be largely wrong. It is not what each hemisphere does—they are both involved in everything—but how it does it that matters. And the prime difference between the brain hemispheres is the manner in which they attend… The result is that one hemisphere is good at utilizing the world, the other better at understanding it… This book helps you to see what you have been trained not to see by our very unusual culture.

Iain McGilchrist, Ways of Attending, 2019

Until recently, I was wary of brain research because so much of it is rooted in the assumption that the human mind is the product of the brain. But the extensive research of Iain McGilchrist, as documented most especially in his book, The Master and His Emissary, gives credence to the view that the brain is a mediator of the mind—actually, two minds. Brain researchers like McGilchrist, and the ones he references, no longer conceive of the left and right hemispheres in terms of distinct functions, but of two different ways of knowing and being.

I began as an artist who simply loved to create paintings and sculptures. However, over the years, I became increasingly interested in the inner activity behind the outer, creative activity of painting and sculpting—namely, the way I observe, think, feel and will. Especially through teaching art, I came to appreciate how artistic capacities are relevant not only for artists making works of art, but also for all people in all walks of life. After all, the cultivation of scientific capacities is not limited to professional scientists; they are developed in most human beings so they can serve and function within our global technological civilization. Developing the inherent scientific capacities dormant in every human being is an enterprise that has slowly evolved over several centuries, if not the last 2500 years. Education as we know it is concerned almost exclusively with developing what are commonly referred to as STEM capacities: scientific, technological, engineering and mathematical. More recently, some people, including Yo Yo Ma, advocate for expanding this to STEAM with the inclusion of artistic capacities. The implications of this expansion go well beyond adding more art to the curriculum; it opens up a new educational paradigm that focuses less on content and more on the capacities we develop—artistic as much as scientific—through the way we approach each discipline.

We stand at the beginning of the next great human enterprise of cultivating the artistic capacities dormant in every individual as the complement to the scientific capacities we are already developing in each individual. We will cultivate the artist in each individual for its own sake, but also in order to draw upon the full scope of our human potential in understanding and resolving the many challenges of contemporary life.

It is very powerful to have a scientist and brain researcher like McGilchrist show, with extensive evidence, that the dominance of our mechanistic, left-hemisphere thinking is the root cause of serious risks to human life and civilization that are becoming evermore apparent with each passing day. To counter these existential threats and rescue our one-sided and “very unusual culture,” we must make a concerted and sustained effort to cultivate the living, intuitive capacities of the right hemisphere. Exactly a hundred years ago, Rudolf Steiner drew attention to the significance of an artistic way of knowing in one of the Younger Generation lectures:

People say today: he is not a true scientist who does not interpret observation and experiment quite logically, who does not pass from thought to thought in strict conformity with the correct methods that have been evolved. If he does not do this he is no genuine thinker. But, my dear friends, what if reality happens to be an artist and scorns our elaborate dialectical and experimental methods? What if Nature herself works according to artistic impulses? If it were so, human science, according to Nature, would have to become an artist, for otherwise there would be no possibility of understanding Nature. That, however, is certainly not the standpoint of the modern scientist. His standpoint is: Nature may be an artist or a dreamer; it makes no difference to us, for we decree how we propose to cultivate science…

Rudolf Steiner, The Younger Generation, p. 9, Oct. 3, 1922

To clarify the distinction between scientific and artistic capacities, I would like to offer an outline of two different modes of perception, thinking, feeling and willing, followed by a simple form exercise:

Left Hemisphere, Scientific Capacities:

Perception: Exact quantitative perception–to measure, count and weigh;

Thinking: Think critically, analytically, logically, mathematically;

Feeling: Censor feeling as inherently subjective and working against objectivity;

Willing: Act according to mechanistic methods and procedures: thinking will.

Right Hemisphere, Artistic Capacities:

Perception: Exact qualitative perception;

Thinking: Think dynamically, intuitively, synthetically;

Feeling: Transform subjective personal feeling into objective artistic feeling in order to know non-physical qualities and reality;

Willing: Act creatively through living methods and procedures: feeling will.

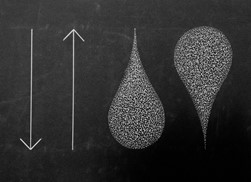

Figures 1a and 1b are familiar arrow forms, one pointing down and the other pointing up. Form 1c looks like a raindrop and 1d reminds us of a balloon. It is natural for our thinking to attach such concepts to everything we perceive, but how do we experience such forms with our feeling?

In the first instance, we may simply like certain forms and dislike others. The arrow forms may not evoke any particular feeling, as we simply think down and up. With the raindrop we may also think down, but we may notice that this is related to our feeling a downward movement. This becomes all the more vivid when we feel an upward movement with the balloon form. If we attend to the form elements of each form, we will see that the sense of movement in 1c and 1d has to do with them being curved rather than straight, but more specifically, with where they are widest—below the middle for the raindrop and above the middle for the balloon.

This simple form exercise engages a capacity that Rudolf Steiner calls artistic feeling:

We will not come to a true understanding of this matter if, in looking at the forms, we base it only on an intellectual explanation. We must look into the forms with artistic feeling and allow the capitals, as form, to work upon us.

Rudolf Steiner, Introduction to Images of the Munich Congress Seals and Capitals, October 1907 (included in Rosicrucianism Renewed)

Rudolf Steiner uses “artistic feeling” in a specific way that I understand to mean:

Artistic feeling is the capacity to set aside one’s personal feelings of like/dislike in order to feel and experientially know the non-physical qualities inherent to all realms of existence—the inanimate, the animate, the ensouled and the spiritual.

This artistic way of perceiving and knowing is foundational to the cultivation of Goethean science and spiritual science. Artistic feeling expands the scope of our conscious experience beyond a narrowly materialistic way of knowing to all-encompassing spirit knowing.

What we need is not repudiation of science but rather, on the contrary, a carrying forward of the future-bearing, objective spirit of science into the realms of qualitative experience, and into the domains of life, soul and spirit that have been hitherto inaccessible to scientific investigation…

The intensification and deepening of sense perception in the arts will go hand and hand with the development of a physiognomic (Goethean) science that will be able to recognize and assess the qualitative aspects of the phenomena just as we today subject them to quantitative analysis.

John Barnes, The Third Culture

There is more that can be said about how this artistic way of knowing is evolving both within and outside Waldorf and anthroposophical circles. For now, I will round off this article by drawing attention to the deeper human significance of developing scientific capacities that will be further enhanced by developing our inherent, artistic capacities.

Science has dramatically changed the outer world we live in, but even more significantly, it has facilitated an inner change in ourselves. The inner activity of developing scientific ways of observing, thinking and doing over the last few centuries has been a primary

way for humankind to awaken and develop our spirit individuality. Ironically, our plunge into materialism arose out of a spiritual need. The inner activity of learning to perceive, think, feel and act in a scientific manner not only allowed us to master the laws and forces of the outer material world, it necessitated a strengthening of our spirit individuality. In the past, the development of our individuality remained largely unconscious; today we are entering a phase in human evolution in which the development of our spirit individuality will become increasingly conscious and self-initiated. Furthermore, the next step in this development of spirit individuality will occur through our self-initiated nurturing of artistic ways of perceiving, thinking, feeling and willing to balance and complete the development of our scientific capacities.

Having considered artistic feeling as a way of knowing in general, the next article will look at self-knowledge and self-development as an artistic activity requiring artistic capacities, particularly when it comes to developing the inner freedom of our spirit self.