Dear BACWTT Students, Alumni, Friends and Colleagues,

Here is the verse from the Calendar of the Soul for this week:

Verse 44

Firm grows the power of thought

In union with the spirit birth

And senses’ dull enchantment

It brightens to full clarity.

If richness of the soul

Would join with world becoming,

Then senses’ revelation

Must needs receive the light of thinking.

In the German original, the expression “firm grows the power of thought” is more like “consolidated becomes the power of thought.” We can sense more in the German with this sense of consolidation, which has a feeling of gathering and condensing, centering and structuring. This is helpful when considering the changes taking place in our thinking during this season, and the effect this can have upon the senses that have become a bit dreamlike and inward-looking during the winter months.

The second part of the verse builds on this, but starts with the word “if” to make sure we know that this will not necessarily happen by itself – that it will require our effort. If we want to be able to build a bridge between our rich, inner world and the outer world that is calling to our senses, then the senses and thinking must be connected – inner “richness” connected with thinking’s “light.”

Steiner brings into this week’s verse the idea of “enchantment” – that our sense have become “enchanted” and that we should “disenchant” them. This is a different understanding behind the word than what is used in everyday speech – we rarely use the word in this way, and Steiner is drawing our attention to something different.

One aspect of this comes to us through ancient stories, and has to do with the idea of something being put under a spell. In fairytales, it is often a witch that casts a spell placing people and locations into a condition where they cannot see through to reality or act out of their true nature. In the fairytale, Briar Rose becomes enchanted into a 100-year sleep after she pricks her finger on a spindle that has a spell placed upon it by an angered wise woman. The 100-year enchantment wears off and is broken by the timely appearance and kiss of a passing prince.

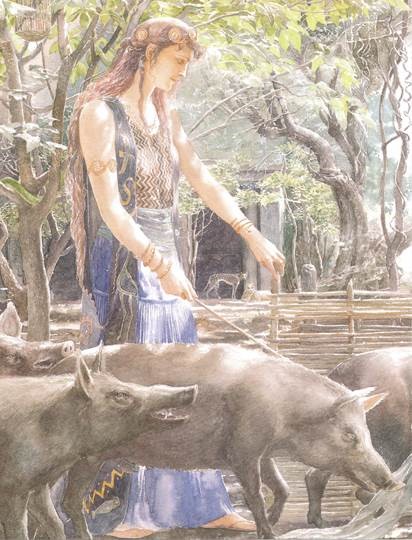

Circe, a minor goddess in Greek mythology, was renowned for her vast knowledge of potions and herbs. Through the use of these and a magic wand or staff, she would transform her enemies or those who offended her into animals. In The Odyssey, when Odysseus visits the island of Aeaea on the way back from the Trojan War, Circe changes most of his crew into swine and keeps Odysseus trapped on the island. Odysseus is also placed under an enchantment by Calypso, binding him and his crew to the island. According to Homer, Calypso enchants Odysseus with her singing as she moves to and fro, weaving on her loom with a golden shuttle. She keeps Odysseus prisoner at Ogygia for seven years.

However, Rudolf Steiner brings a whole new understanding to this term “enchantment,” which is a key to discovering his intention in the arts.

In his lecture about art, “The Physical-Superphysical: Its Realization Through Art,” Munich, 15th February, 1918 (also known as “The Two Sources of Art, Impressionism and Expressionism”), he connects the efforts of Goethe and modern impressionist artists to break through the outer veil of the natural world and to express the forces and realities that are hidden within it.

“By setting free what has been enchanted into nature, we at the same time break nature up into her super-physical forces. Then there is no need to seek through dry allegory, nor in a way that is intellectual and without artistic feeling, for any idea, anything thought out, anything purely superphysical and spiritual, behind the objects of nature. One just asks nature quite simply: How would you develop in your various parts were your growth undisturbed by a higher life? We come to the rescue of something superphysical that has been held in the physical by enchantment and free it from the physical bonds that held it spellbound. We actually come to be naturalistic in a supernatural way. I believe that in all the various tendencies and endeavors of recent times, still very much in an elementary stage, which call themselves impressionism, I believe we may perceive in all these the longing of our time really to discover and give shape to secrets of this kind, to this kind of physical-superphysical. For a feeling is abroad that what is actually accomplished in art — in artistic creation and in the appreciation of art — must today be raised into fuller consciousness than has been the case in former epochs.”

“The reason why nature — not now in an outward, spatial way but inwardly and more intensively — seems to us so magical, so mysterious, is because in each of her works she is wanting to offer us more, infinitely more than she can, and because she puts together her several parts, all that she organizes, in such a way that a higher life swallows up the life inferior to it, allowing it only partial development. Whoever directs his perception to this, will everywhere find that this open secret, this magical quality running through the whole of nature is — like the inward striving after the vision, but here working from outside — what stir a man up to take his stand somewhere beyond nature, to choose something special out of the whole, and from there to let shine forth what nature is seeking to do in one of her works — what can become a whole but has not become so in nature herself.”

There is something in this thought that is opposite to the well-known quote, “The sum is greater than the parts,” attributed to Aristotle, that Steiner is articulating here. It is the thought that the parts, in uniting to create a greater whole, have given up some of their own inherent possibility. This coming together to allow for a higher principle to take hold, to incarnate, has caused the elements of that greater form to become “enchanted.” The artistic intention of impressionism is to give these subsumed aspects the interest and attention that frees them from the restrictions the nature places upon them.

Steiner attempted to work in this way in his own artistic works – in painting, sculpture and architecture – to release the true forms of things that are trapped in the necessary forms imposed upon them by nature, allowing them to express themselves and then bringing them to an artistic depiction. He speaks here about this in the creation of the large wooden sculpture in the Goetheanum:

“Perhaps I may mention here that in the Anthroposophical Society’s building at Dornach, near Basle, an attempt has been made to realize in plastic [sculptural] form all that has just been indicated. We have tried to make a sculptural group in wood to represent what may be called the typical man; but this group represents the typical man in such a way that what otherwise is only tendency, and held in check by higher life, first comes to expression in the whole form only in gesture which is then brought back into a state of rest. The endeavor has been made plastically to awaken this gesture which in the ordinary human being is kept under — not the gesture made by the soul but the one that is killed [subsumed] before it leaves the soul, the one held under by the life of the soul — and then to bring it to rest again. Thus it has been sought first to set the resting surface of the human organism in movement through gesture and then to return it to a state of repose. Through this one came quite naturally to see that something had to be given greater prominence.”

In this same lecture, he points to the other approach to artistic work – expressionism – and how these two streams in art are really needed for well-being in our time; how they support and bring health to our experience of the outer world of nature and the inner world of the soul. This sense for the importance of the arts that are held and practiced in this way underlies the art that children do in Waldorf schools – on the one side, living into and allowing glimpses into the mysteries of nature; on the other side, allowing the stirrings of the soul to rise up into creative imaginations. Steiner suggests that artistic activities done in these two ways are needed for health in modern times.

Waldorf education is a kind of rich soup comprised of all the remarkable initiatives that Steiner began in his lifetime. Many of the elements of this soup have become difficult to discern now 100 years later and, excuse the analogy, the soup has been in the pot for so long that it has become a little mushy! In our teacher training program, we are continuously trying to get behind and beneath the Waldorf curriculum – to find the clearly cut and firm elements of Anthroposophy, to grasp them sufficiently so that they can then be appropriately rendered for children.

So the verse this week is a prompt to recall this aspect of our work in the sciences – from 4th Grade Human and Animal through Botany, Geography and Geology, Physics and Physiology and Chemistry and on; that the artistic aspect of these lessons is not (only) there to make it attractive, creative and individual, but has this deeper quest to connect to the “open secrets,” as Goethe calls them, to lead the young student not only into the realities of the physical world, but also towards the realities within and behind them.

Ken

Kenneth Smith

Director

BACWTT